Online first

Current issue

Archive

Special Issues

About the Journal

Publication Ethics

Anti-Plagiarism system

Instructions for Authors

Instructions for Reviewers

Editorial Board

Editorial Office

Contact

Reviewers

All Reviewers

2025

2024

2023

2022

2021

2020

2019

2018

2017

2016

General Data Protection Regulation (RODO)

RESEARCH PAPER

Place of residence and time of day as factors affecting the course of vaginal delivery

1

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Didactics, Faculty of Health Sciences, Medical University, Warsaw, Poland

2

Department of Human Anatomy, Faculty of Health Sciences, Medical University, Warsaw, Poland

3

Department of Emergency Medical Services, Faculty of Health Sciences, Medical University, Warsaw, Poland

4

Department of Midwifery, Centre f Postgraduate Medical Education, Warsaw, Poland

Corresponding author

Grażyna Bączek

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology Didactics, Faculty of Health Sciences, Medical University of Warsaw,, Warsaw, Poland

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology Didactics, Faculty of Health Sciences, Medical University of Warsaw,, Warsaw, Poland

Ann Agric Environ Med. 2022;29(4):554-559

KEYWORDS

TOPICS

ABSTRACT

Introduction and objective:

Childbirth is one of the most important events in a woman’s life and is influenced by many factors. The aim of the research was to analyze the impact of the place of residence of women giving birth and the time of day on the course of natural birth.

Material and methods:

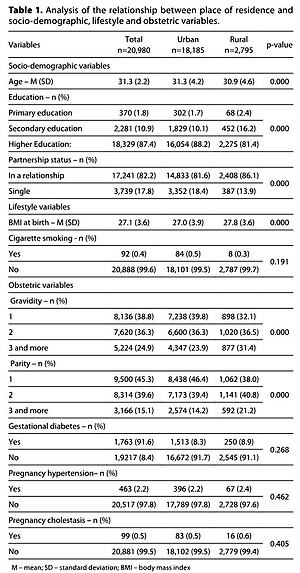

The study was conducted using the method of analysis of retrospective electronic documentation of patients who gave natural vaginal birth in the St. Zofia hospital in Warsaw, Poland. The analysis covered the period from 1 January 2015–31 December 2020; from 40,007 cases, 20,980 were qualified for final analysis. Analysis of the documentation allowed to obtain the following data: socio-demographic, lifestyle, obstetrics, course of delivery and the condition of the newborn. Analysis of the relationship between qualitative variables was performed using the Chi-square test, while the Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare two quantitative variables.

Results:

Women giving vaginal delivery from rural areas were younger (30.9 vs. 31.3), had primary education (2.4% vs. 1.7%) and secondary education (16.2% vs. 10.1%), were in a relationship (86.1% vs. 81.6%) and more often had a higher BMI at birth (27.8 vs. 27.0), compared to the patients living in cities (p<0.05). In addition, between 07:00–18:59., induction of labour (20.7% vs. 19.1%), epidural anesthesia (35.4% vs. 34.0%) and episiotomy were performed more often (29.1% vs. 27.8%) (p<0.05).

Conclusions:

Differences were shown in the course of vaginal delivery in relation to the place of residence of the women, and the time of day of the delivery. These factors should be considered in the planning of perinatal care. At the same time, it is necessary to conduct further research on the analyzed aspect in order to ensure the highest quality care.

Childbirth is one of the most important events in a woman’s life and is influenced by many factors. The aim of the research was to analyze the impact of the place of residence of women giving birth and the time of day on the course of natural birth.

Material and methods:

The study was conducted using the method of analysis of retrospective electronic documentation of patients who gave natural vaginal birth in the St. Zofia hospital in Warsaw, Poland. The analysis covered the period from 1 January 2015–31 December 2020; from 40,007 cases, 20,980 were qualified for final analysis. Analysis of the documentation allowed to obtain the following data: socio-demographic, lifestyle, obstetrics, course of delivery and the condition of the newborn. Analysis of the relationship between qualitative variables was performed using the Chi-square test, while the Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare two quantitative variables.

Results:

Women giving vaginal delivery from rural areas were younger (30.9 vs. 31.3), had primary education (2.4% vs. 1.7%) and secondary education (16.2% vs. 10.1%), were in a relationship (86.1% vs. 81.6%) and more often had a higher BMI at birth (27.8 vs. 27.0), compared to the patients living in cities (p<0.05). In addition, between 07:00–18:59., induction of labour (20.7% vs. 19.1%), epidural anesthesia (35.4% vs. 34.0%) and episiotomy were performed more often (29.1% vs. 27.8%) (p<0.05).

Conclusions:

Differences were shown in the course of vaginal delivery in relation to the place of residence of the women, and the time of day of the delivery. These factors should be considered in the planning of perinatal care. At the same time, it is necessary to conduct further research on the analyzed aspect in order to ensure the highest quality care.

REFERENCES (39)

1.

Larkin P, Begley CM, Devane D. Women’s preferences for childbirth experiences in the Republic of Ireland; a mixed methods study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):19. doi:10.1186/s12884-016-1196-1.

2.

Joensuu J, Saarijärvi H, Rouhe H, et al. Maternal childbirth experience and time of delivery: a retrospective 7-year cohort study of 105 847 parturients in Finland. BMJ Open 2021;11:e046433. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046433.

3.

Adler K, Rahkonen L, Kruit H. Maternal childbirth experience in induced and spontaneous labour measured in a visual analog scale and the factors influencing it; a two-year cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):415. doi: 10.1186/s12884-020-03106-4.

4.

Lundgren I, Dencker A, Berg M, et al. Implementation of a midwifery model of woman-centered care in practice: Impact on oxytocin use and childbirth experiences. Eur J Midwifery. 2022;6:16. doi: 10.18332/ejm/146084.

5.

Sys D, Kajdy A, Baranowska B, et al. Women’s views of birth after cesarean section. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2021;47(12):4270–4279. doi: 10.1111/jog.15056.

6.

Deys L, Wilson PV, Meedya DS. What are women’s experiences of immediate skin-to-skin contact at caesarean section birth? An integrative literature review. Midwifery. 2021;101:103063. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2021.103063.

7.

Genowska A, Zalewska M, Jamiołkowski J, et al. Inequalities in mortality of infants under one year of age according to foetal causes and maternal age in rural and urban areas in Poland, 2004–2013. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2016;23(2):285–291. doi: 10.5604/12321966.1203892.

8.

Guarnizo-Herreno CC, Torres G, Buitrago G. Socioeconomic inequalities in birth outcomes: An 11-year analysis in Colombia. PLoS One. 2021;16(7):e0255150. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0255150.

9.

Lisonkova S, Razaz N, Sabr Y, et al. Maternal risk factors and adverse birth outcomes associated with HELLP syndrome: a population-based study. BJOG. 2020;127(10):1189–1198. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.16225.

10.

Daoud N, O’Campo P, Minh A, et al. Patterns of social inequalities across pregnancy and birth outcomes: a comparison of individual and neighborhood socioeconomic measures. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;14:393. doi: 10.1186/s12884-014-0393-z.

11.

Scarf VL, Rossiter C, Vedam S, et al. Maternal and perinatal outcomes by planned place of birth among women with low-risk pregnancies in high-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Midwifery. 2018;62:240–255. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2018.03.024.

12.

Amjad S, Chandra S, Osornio-Vargas A, et al. Maternal Area of Residence, Socioeconomic Status, and Risk of Adverse Maternal and Birth Outcomes in Adolescent Mothers. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2019;41(12):1752–1759. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2019.02.126.

13.

Dongarwar D, Salihu HM. Place of Residence and Inequities in Adverse Pregnancy and Birth Outcomes in India. Int J MCH AIDS. 2020;9(1):53–63. doi: 10.21106/ijma.291.

14.

Kaur S, Ng CM, Badon SE, et al. Risk factors for low birth weight among rural and urban Malaysian women. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(Suppl 4):539. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6864-4.

15.

Ospina M, Osornio-Vargas ÁR, Nielsen CC, et al. Socioeconomic gradients of adverse birth outcomes and related maternal factors in rural and urban Alberta, Canada: a concentration index approach. BMJ Open. 2020;10(1):e033296. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033296.

16.

Auger N, Authier MA, Martinez J, et al. The association between rural-urban continuum, maternal education and adverse birth outcomes in Québec, Canada. J Rural Health. 2009;25(4):342–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2009.00242.x.

17.

Cappadona R, Puzzarini S, Farinelli V, et al. Daylight Saving Time and Spontaneous Deliveries: A Case-Control Study in Italy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(21):8091. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17218091.

18.

Larcade R, Rossato N, Bellecci C, et al. Gestational age, mode of delivery, and relation to the day and time of birth in two private health care facilities. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2021;119(1):18–24. doi: 10.5546/aap.2021.eng.18.

19.

Gould JB, Abreo AM, Chang SC, et al. Time of Birth and the Risk of Severe Unexpected Complications in Term Singleton Neonates. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;136(2):377–385. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003922.

20.

Lee GY, Um YJ. Factors Affecting Obesity in Urban and Rural Adolescents: Demographic, Socioeconomic Characteristics, Health Behavior and Health Education. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(5):2405. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18052405.

21.

Lee H, Lin CC, Snyder JE. Rural-Urban Differences in Health Care Access Among Women of Reproductive Age: A 10-Year Pooled Analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(11 Suppl):S55-S58. doi: 10.7326/M19-3250.

22.

Howard G. Rural-urban differences in stroke risk. Prev Med. 2021;152(2):106661. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106661.

23.

Genowska A, Szafraniec K, Polak M, Szpak A, Walecka I, Owoc J. Study on changing patterns of reproductive behaviours due to maternal features and place of residence in Poland during 1995–2014. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2018;25(1):137–144. doi: 10.26444/aaem/75544.

24.

Sytuacja demograficzna Polski do 2020 r. Zgony i umieralność. Demographic situation of Poland until 2020 Deaths and mortality. Central Statistical Office, Warsaw 2021.

25.

Richter LL, Ting J, Muraca GM, et al. Temporal trends in neonatal mortality and morbidity following spontaneous and clinician-initiated preterm birth in Washington State, USA: a populationbased study. BMJ Open 2019;9:e023004. doi:10.1136/ bmjopen-2018-023004.

26.

Trivedi T, Liu J, Probst J, et al. Obesity and obesity-related behaviors among rural and urban adults in the USA. Rural Remote Health. 2015;15(4):3267.

27.

Gallagher A, Liu J, Probst JC, et al. Maternal obesity and gestational weight gain in rural versus urban dwelling women in South Carolina. J Rural Health. 2013;29(1):1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2012.00421.x.

28.

Oladapo OT, Souza JP, Fawole B, et al. Progression of the first stage of spontaneous labour: A prospective cohort study in two sub-Saharan African countries. PLoS Med. 2018;15(1):e1002492. https://doi.org/10.1371/journa....

29.

Xinhua L, Yancun F, Sawitri A, et al. Comparison of Socioeconomic Characteristics between Childless and Procreative Couples after Implementation of the Two-Child Policy in Inner Mongolia, China. J Health Sci Med Res. 2020;38(4):285–295.

30.

Szukalski P. Wielodzietność we współczesnej Polsce w świetle statystyk urodzeń. Demografia i Gerontologia Społeczna–Biuletyn Informacyjny. 2018;3:1–6.

31.

Szukalski P. Urodzenia wysokiej kolejności w XXI w. w Polsce. Demografia i Gerontologia Społeczna – Biuletyn Informacyjny 2021;3:1–6.

32.

Rottenstreich M, Futeran Shahar C, Rotem R, et al. Duration of first vaginal birth following cesarean: Is stage of labor at previous cesarean a factor? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;252:344–348. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.06.060.

33.

Grylka-Baeschlin S, Petersen A, Karch A, et al. Labour duration and timing of interventions in women planning vaginal birth after caesarean section. Midwifery. 2016;34:221–229. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2015.11.004.

34.

Lundborg L, Liu X, Aberg K, et al. Association of body mass index and maternal age with first stage duration of labour. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):13843. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-93217-5.

35.

Bohren MA, Hofmeyr GJ, Sakala C, et al. Continuous support for women during childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;7(7):CD003766. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003766.pub6.

36.

Zhang R, Li C, Mi B, et al. The different effects of prenatal nutrient supplementation on neonatal birth weights between urban and rural areas of northwest China: a crosssectional study. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2018;27(4):875–885. doi: 10.6133/apjcn.102017.01.

37.

Zhao X, Xia Y, Zhang H, et al. Birth weight charts for a Chinese population: an observational study of routine newborn weight data from Chongqing. BMC Pediatr. 2019;19(1):426. doi: 10.1186/s12887-019-1816-9.

38.

Mgaya A, Hinju J, Kidanto H. Is time of birth a predictor of adverse perinatal outcome? A hospital-based cross-sectional study in a low-resource setting, Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):184. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1358-9.

39.

Çobanoglu A, Şendir M. Does natural birth have a circadian rhythm? J Obstetrics Gynaecol. 2020;40(2):182–187. doi: 10.1080/01443615.2019.1606182.

Share

RELATED ARTICLE

We process personal data collected when visiting the website. The function of obtaining information about users and their behavior is carried out by voluntarily entered information in forms and saving cookies in end devices. Data, including cookies, are used to provide services, improve the user experience and to analyze the traffic in accordance with the Privacy policy. Data are also collected and processed by Google Analytics tool (more).

You can change cookies settings in your browser. Restricted use of cookies in the browser configuration may affect some functionalities of the website.

You can change cookies settings in your browser. Restricted use of cookies in the browser configuration may affect some functionalities of the website.